Life in his Kalimpong Vihara in the Eastern Himalayas, and on the plains among Dr Ambedkar‘s Buddhist followers, was rich and rewarding. Sangharakshita had no plans to move— until the English Sangha Trust invited him to visit England to spend a few months at the Trust’s Hampstead Buddhist Vihara. Before he left India he learnt from his friend Christmas Humphreys, founder and president of the London-based Buddhist Society, that the tiny British Buddhist world was at odds with itself. Perhaps he could help.

Sangharakshita and visitors outside the Triyana Vardhana Vihara, Kalimpong, India. 1963

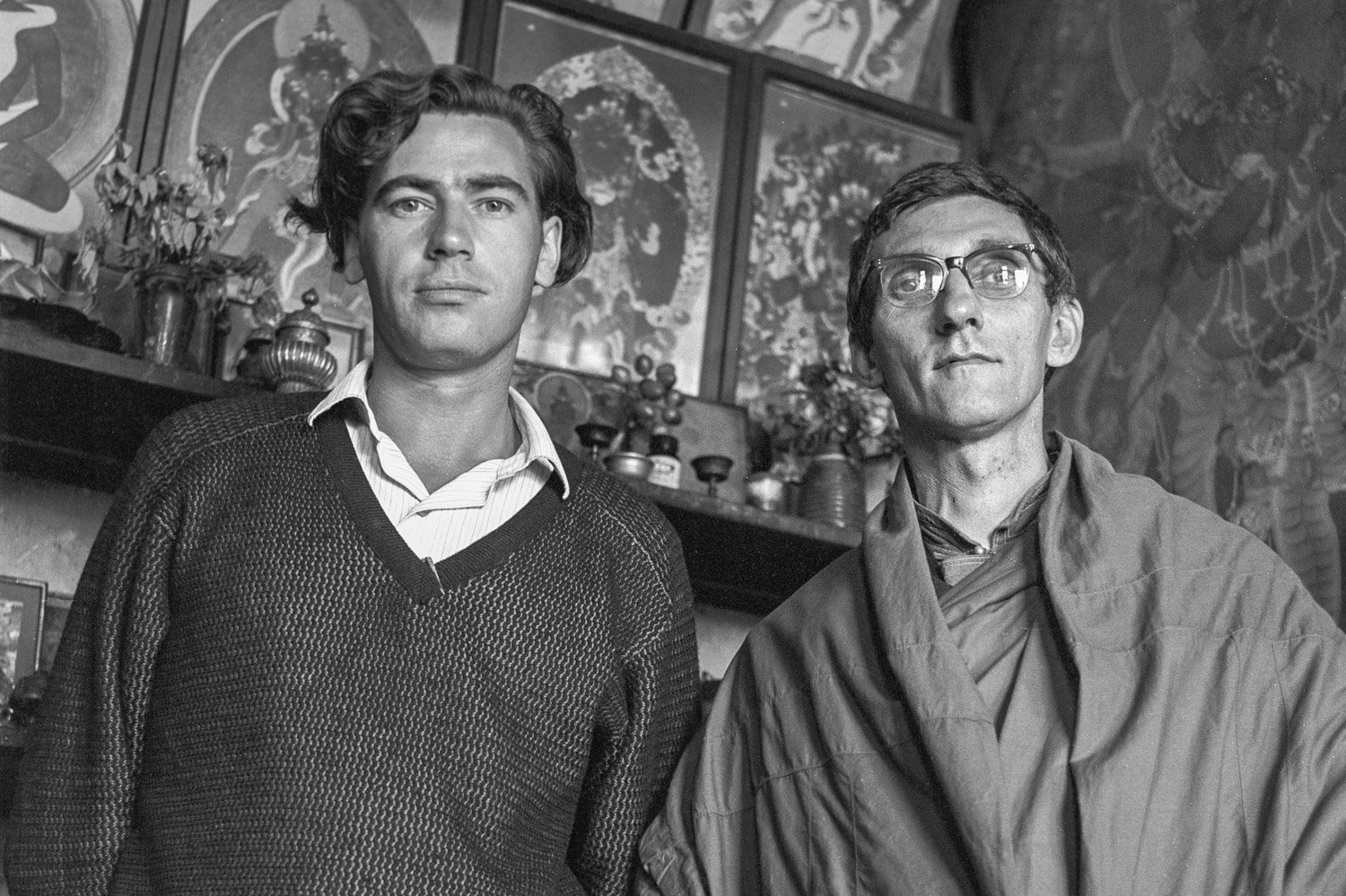

Installed at the Vihara, he gave lectures at the rival London institutions, and visited Buddhist groups around the country. His talks covered basic Buddhist themes while also introducing his listeners to the wealth of the wider tradition. As he adapted to London life and Western ways —something helped along by his close friendship with Terry Delamere — his imagination got to work. Though feeling morally bound to work within the existing institutions, he felt inspired by the potential for an English, even Western, Buddhist movement. He journeyed to India for what he had decided would be a farewell tour, fully expecting to return to England.

Sangharakshita and others at the Hampstead Buddhist Vihara, London, UK. 1966

However, in Kalimpong a letter was waiting for him, from the English Sangha Trust. For vague reasons, it declared, he would no longer be welcomed or supported by the Trust, and was encouraged to continue with his work in India. Perhaps he had offended the extremists in those rival camps, or perhaps he was the victim of some (unfounded) gossip concerning his friendship with Terry Delamere. Either way, he was now free to start a new movement.

Terry Delamare and Sangharakshita.

Kalimpong, India 1966

Loyal friends in London welcomed him back, financed his personal needs, and paid the rent on a small basement room in central London. It was dedicated in April 1987 as the 'Triratna Meditation and Shrine Room'. Sangharakshita continued giving talks, running regular meditation classes and offering occasional country retreats, now under the auspices of the ‘Friends of the Western Sangha’. As he explored ways of communicating the Dharma in a Western context his regular followers settled into and deepened their practice. Within a year, he felt confident that there were enough of them who resonated with, and felt committed to, his approach. In April 1968 he ordained twelve men and women. The Western (today Triratna) Buddhist Order was born.

Triratna Meditation and Shrine Room, London, UK. 1967

The Friends of the Western Buddhist Order, as it was now known, grew slowly, but the next two years were exceptionally creative for its founder. As well as giving talks on Zen, Tibetan Buddhism, the Noble Eightfold Path and the White Lotus Sutra, he explored ways of talking about Buddhism in a naturalised Western language in series on 'The Higher Evolution of Man' and 'The Higher Evolution of the Individual’.

On a personal front he was sharing a flat in North London with two young art students and living, as he might have put it, 'as a bad monk but a good Buddhist’: wearing robes solely in ritual contexts and embarking on a first sexual relationship — with a man..

Sangharakshita teaching on retreat at Keffolds, Haslemere, Surrey, UK. 1968

In 1970, after recovering from a bout of pneumonia which nearly killed him, he took on a three-month visiting professorship at Yale where he relished the energy and bracing directness of young Americans. All the same, he returned to England where some of those first Order members had kept things going in his absence. Attendance at classes was growing…

Nagabodhi

Yale University, USA. May 1970

Letter from Christmas Humphreys dated 29/5/1963

Christmas Humphreys (1901-1983) was a British barrister and High Court judge. In 1924 he founded the Buddhist Society, a non-sectarian organisation of which he remained the President until his death. His best-selling book Buddhism, published in 1962, ‘probably introduced more people to the Buddha and his teachings than had any other book since the publication of Sir Edwin Arnold’s The Light of Asia in 1879’. His particular interest was Zen.

This four-page letter, written to Sangharakshita when he was still living in Kalimpong, outlines the difficulties then current between the English Sangha Association and the Buddhist Society. Humphreys expresses his confidence in Sangharakshita as one of the few men capable of taking up the ‘difficult job’ of restoring harmony between them.